There’s a question for the Consult-Ant this week. (The “Consult-Ant” started on the Leaping from the Box website, where I answered questions about ants and ant farms. From now on I will post the answers here, and when Karen has time she will also post the answers on her site.)

Question: I have an ant question!

I have been observing common ants foraging and wonder what range their senses have to understand their foraging tactics. Presumably they are hoping to discover a food source.

Mike.

Answer:

Wouldn’t it be cool to be able to slip into a creature like an ant and experience the world through their senses?

Unfortunately, we aren’t quite there yet. Scientists are making some breakthroughs in understanding how ants perceive the world, but there are still many, many questions. To make things even more complicated, it appears that different species of ants have different sensory abilities, so there isn’t just one answer as to how ants’ senses work.

Although ants have a variety of senses, most ants probably use a combination of vision and olfaction to find their food. Let’s explore those two in more detail.

1. Vision

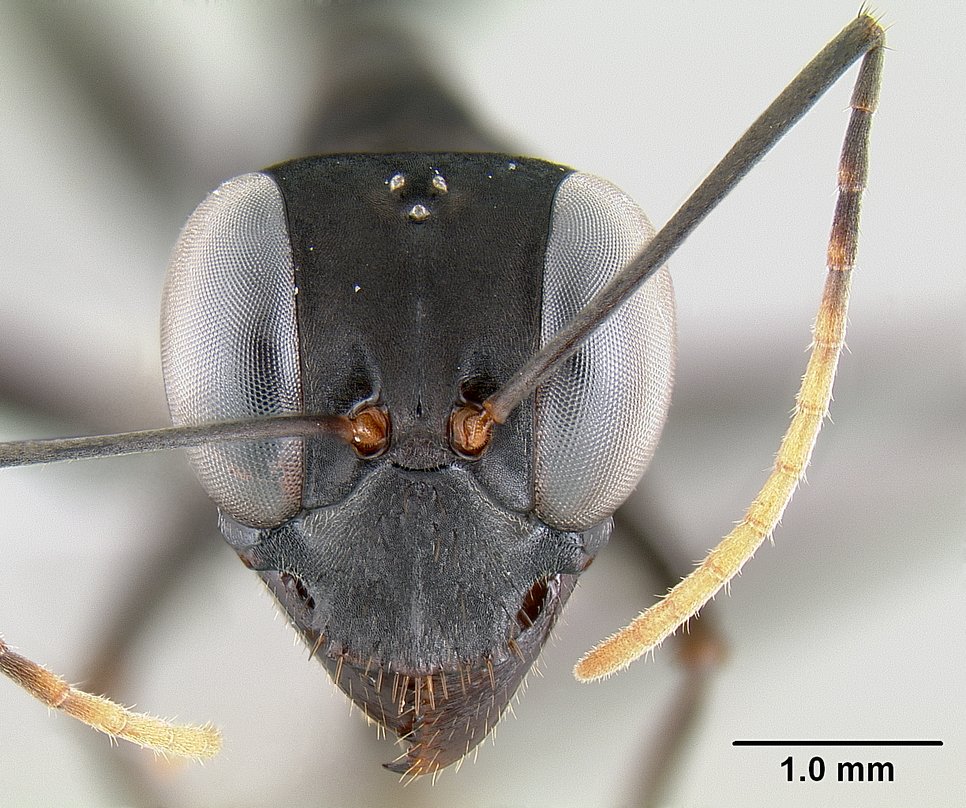

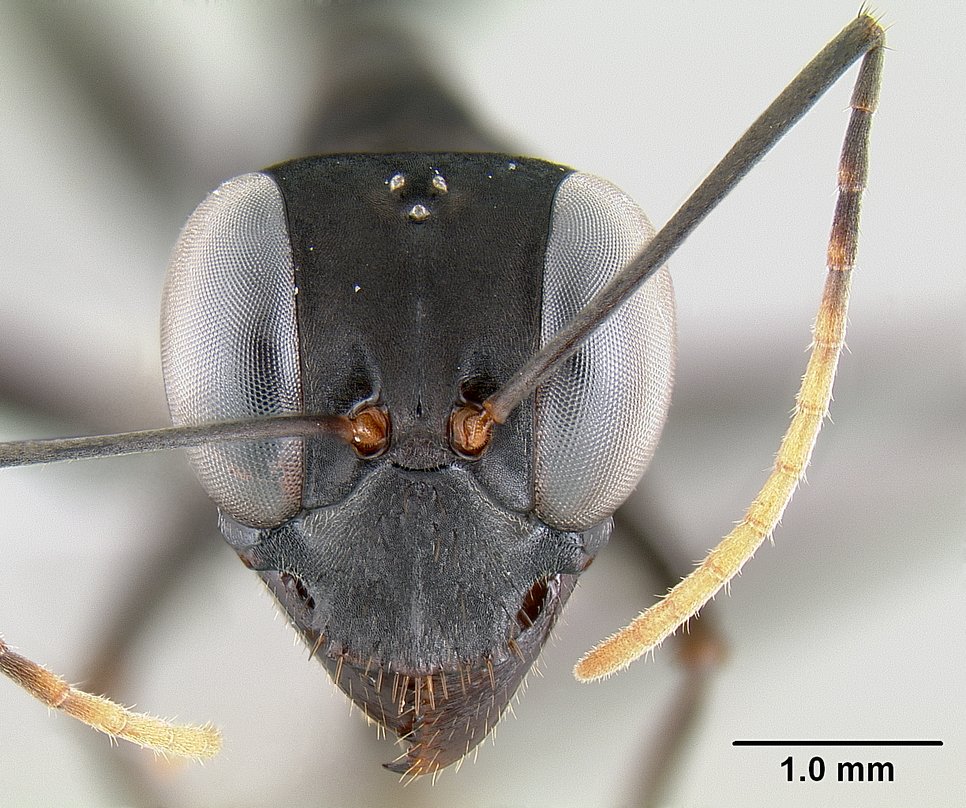

Without even knowing how ants’ eyes work, we can see there are big differences in the structure.

For example, this ant has massive eyes.

(Gigantiops destructor Photographer: Michael Branstetter Date Uploaded: 07/20/2009 Copyright: Copyright AntWeb.org, 2000-2009. Licensing: Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 (cc-by-sa-3.0) Creative Commons License)

(Gigantiops destructor Photographer: Michael Branstetter Date Uploaded: 07/20/2009 Copyright: Copyright AntWeb.org, 2000-2009. Licensing: Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 (cc-by-sa-3.0) Creative Commons License)

This huntress has normal-sized eyes.

Army ants have reduced eyes or are even blind.

(Public domain photograph of Eciton burchelli by Alex Wild)

(Public domain photograph of Eciton burchelli by Alex Wild)

For ants with well-developed eyes, we would expect that since they are small and close to the ground, perhaps they can’t see far. In fact, Marie-Claire Cammaerts (2004) found Myrmica sabuleti ants could discriminate objects 15 cm away, but only 10 cm above. On the other hand, bulldog ants in the genus Mymecia have excellent vision and have been reported to be able to see a meter away.

How do ants use vision for foraging? Not only can they spot prey, but also according to Hölldobler and Wilson (1990) foraging worker ants can learn/remember to return to places where they found food in the past using visual cues. Researchers have found some species of ants can orient to food sources using the the skyline (Graham and Cheng, 2009), or polarized light (for example Krapp 2007, Wehner et al. 2014). So, they may see farther than we might expect.

Related:

2. Sense of smell – Olfaction

Blind ants — or those that forage at night — may use their sense of smell to find food. Insects detect odors largely with their antennae.

How do the antennae work? Within the antennae are odor receptors that can bind with specific free-floating molecules. When the correct molecule bumps into and binds with the receptor, a nerve associated with it sends a signal to the mushroom bodies in the insect’s brain, where it is processed or identified.

From how far away can ants detect smells? It really depends on how far the odor molecules can travel. I wasn’t able to find much about detection distances for ant antennae, but male moth antennae can detect female moth pheromones from 300 feet away.

What kinds of things can they smell? Zwiebel at al. (2012) found over 400 different odor receptors in each of two species of ants: a carpenter ant, Camponotus floridanus, and the Indian jumping ant, Harpegnathos saltator. Using an unusual bio-assay involving frog eggs they discovered that although the receptors were equally numerous in both species, the odors detected by the receptors were not the same. For example, the jumping ant could detect a component of anise (a spice), whereas the carpenter ant could detect an odor from cooked pork. Presumably those differences reflect differences in their biology or environment.

According to the same article, ants also have gustatory receptors, which distinguish taste (among other things). In addition, they have ionotropic glutamate receptors that can detect toxins and poisons. This can be important for seed-harvesting ants and leaf cutter ants because plants may contain toxins that will either harm the ant larvae, or the fungus that leaf cutter ants garden for food.

3. Scouting for Food?

“Presumably they are hoping to discover a food source.”

Yes, when they are outside the nest, by-and-large foraging ants are looking and smelling for food. (Although a few may be scoping out potential enemies as well.)

Again, the process varies depending on what kind of ant you have. Some ants are solitary hunters. Each ant hunts and brings food back on its own, whether seeds or insect prey. In some species, special scouts search for food and return to the nest once they find it. They recruit other foragers to retrieve the food. Often the strategy will be intermediary, and depend on the size or quantity of food on a given day.

Although most ants are omnivores, what constitutes food will also vary and those differences will change how ants detect it. For example, ants that tend aphids or leafhoppers may locate potential food by smelling honeydew that has dropped to the ground under the plant where the insects are feeding.

Conclusion

The bottom line is that how an ant finds food will be limited by the range of its senses, but right now we don’t have a complete picture of what those limits are. Personally, I would not be surprised if we discover that certain ants have some amazing abilities that we haven’t even thought to look for yet.

_________

Hopefully, that answers your question at least in part.

Does anyone else have anything to add to help Mike?

The worker ants scurried to remove the brood to safety.

The worker ants scurried to remove the brood to safety. Maybe it will be clearer here. Notice the workers are rushing to hide the pupae.

Maybe it will be clearer here. Notice the workers are rushing to hide the pupae.